Queer Britain – Queer Museums and Archives

Homotopia in Liverpool have been pioneers in driving debate. At their conference ‘The Un-straight Museum’ in 2014 they brought together a wide cross section from cultural institutions, curators, and archivists in representing marginalised communities and promoting diversity. What emerged from that conference was a picture of (mostly) LGBTQ professionals and activists who were propelling change within these bodies but often in the face of resistance and incomprehension from more senior staff and little in the way of financial resources.

State funded bodies had taken on board the changes in government directives that required them to show that they were serving minority communities, and realising they needed to demonstrate how they made their displays accessibility to LGBTQ visitors. Some were very proactive, attempting to identify and re-catalogue objects with LGBTQ relevance. Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery for instance won funding to begin to clearly flag queer objects of this type and to make them routinely part of the collecting policy. The Museums of Liverpool has held a number of specific exhibitions that made them inclusive of the un-straight viewer.

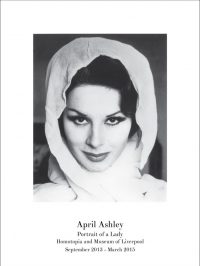

Examples include ‘April Ashley; Portrait of a lady’ (Museum of Liverpool, Sept 2013 to March 2015), and ‘Coming Out, Sexuality, Gender and Identity’ (Walker, 28 July – 5 November 2017). The latter show and The Tate’s ‘Queer British Art’ curated by Clare Barlow, were major ground breaking exhibitions made for the 50th anniversary of the passing of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalising gay sex. Other Cities including Manchester and Brighton have also seen pioneering museum shows but the fact that they have strong visible LGBTQ communities, with local vocal pressure for change, is largely responsible for a better understanding of the need for inclusion.

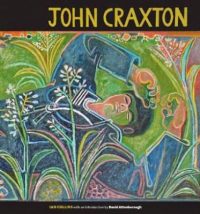

It is still the case that a degree unconscious heterosexist presumption ‘forgets’ to consider if an item or LGBTQ strand should or could be drawn out. Too often this element of their program is confined to Pride month and not integrated into the institution as a whole. The unconscious bias is most noticeable with biographical details in exhibit narratives where a double standards are applied. To give an example, the British Museum is, as I write this, featuring an exhibition ‘Charmed lives in Greece’ it features the artists Ghika, John Craxton and writer Patrick Leigh Fermor. Craxton’s work is strongly homoerotic, in particular his depiction of Greek sailors. Whilst both other artists have plenty of attention paid to their wives and loves Craxton is portrayed as somehow single and his images of sexy men are left unexplained. The usual euphemisms of ‘deep friendships’ and ‘love of Greek people/landscape’ but the only mention that he was gay is a time line note that he was survived by his partner Richard Riley. His love of cats is deserving of comment but not that of the sailors.

When the ceramicist Matt Smith was artist in residence at the Victoria & Albert Museum he made a point of looking for object labels that drew out relevant information and narratives around LGBTQ artists, themes or subjects. He found two. When he queried this with a group of senior curators the response, as he described it, amounted to a mystified “so?” These museums have curators who have specific fields of knowledge, experts in anything from Renaissance ironwork to jewellery. They do not have Curators of the Queer. This is usually relegating this to the Education Department and outreach. That is why we need our own centres of excellence and knowledge.

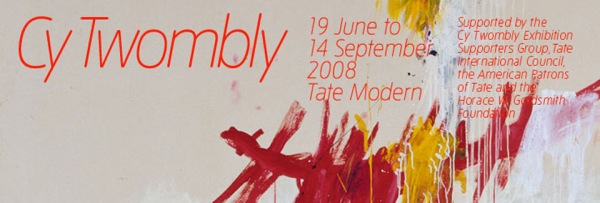

When Tate Modern showed Cy Twombly in 2008 captions referred to his wife in respect to relevant paintings but made no mention of his sexual relationship Robert Rauschenberg (in respect of an important suite of painting directly relating to their affair) or his long term partner Nicola Del Roscio.

At the conference ‘Civil Partnerships? Queer and Feminist Curating’ (2012, hosted at Tate but actually organised by the University of Brighton), the queer artist, curator and writer Michael Petry read out a letter he received from Nicholas Serrota when he queried this omission. The response basically admitted the bias towards only heterosexual acknowledgement and shrugged. More recently Agnes Martin was similarly whitewashed. Curators tiptoe around intimate details for fear of artists families and collectors, avoiding queer readings. Frankly this diplomatic straightening of bent readings is conservative, cowardly and political.

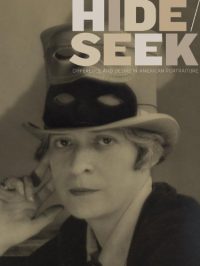

When art historian Jonathan Katz attempted to get the exhibition Hide/Seek hosted at American museums he found almost every major institution refused to countenance the idea. Securing loans was difficult because neither museums nor collectors wanted their artworks associated with homosexuality. Many private collectors felt it might affect their properties saleability – something which had to be delicately negotiated round with Tate’s Queer British Art. The National Portrait Gallery to their credit did agree to host the show but when Republican House Speaker John Boehner and the Catholic League attacked it the Smithsonian forced the withdrawal from view a video by the artist David Wojnarowicz (Fire in My Belly). Katz is scathing in his criticism of homophobia and closeting of LGBTQ artists in American institutions.

The attack on the Washington exhibition focused on works deemed to be obscene or blasphemous and this is another reason we need spaces unafraid of unapologetic, unambiguous displays. Such a venue can be a source of expertise and understanding that is lacking in state institution and those that are heavily reliant on patrons with homophobic attitudes. The preservation of material that is ‘problematic’ is also one that a specific LGBTQ museum could address. At present it is almost impossible to persuade state museums that explicit sexual material should be conserved and shown. Even relatively inoffensive items are too often relegated to ‘adult material’ rooms that are not applied to heterosexual equivalents. Not just that but the social history perspective, what Michael Petry wrote about in his ‘Hidden Histories’ and what Emmanuel Cooper termed the sexual perspective, a queer sensibility, have hardly been exposed to public gaze in a way that bridges communities without pandering only to the majority.

Most institutions that do unapologetically celebrate the queer view are private foundation or charities. Examples include The Tom of Finland Foundation, The Leslie + Lohmann Museum (now with recognised Museum status) and the Bob Mizer Foundation. Doing fine things they struggle to keep going, usually reliant on volunteers, donations or income from estate copyrights.

It is often individuals to found these projects: those with a passion for the subject and respect for it. In Australia Michael Carnes and Robert Lavis became so frustrated at the lack of respect for gay erotic art, that they have been gradually building a collection towards a private museum. As independent collectors they demonstrate their impatience with prurient institutional approaches and an ‘out’ attitude through their collections title COME (Collection of Male Erotic Art). Many individuals preserve material which is in danger of being lost for want of a safe place for it to be consigned. In Germany the Schwules Museum of Berlin has achieved a degree of stability with cultural funds of the Berlin Senate but it is rare to find a welcome for material and persuade institutions to take it in.

Archives are usually reliant on subsidiary funding, often linked with university collections. In America, universities with strong queer study collections and archives are usually those sited near gay city strongholds: queer staff and students exert pressure to collect and create specialist centres of excellence. In London the Hall Carpenter Archives (actually with little relating the pioneers of the title) is housed within the London School of Economics. Others regarded as extremely friendly and pro-active with LGBTQ material include The London Metropolitan Archive and The Bishopsgate Institute. But a problem with others is again recognition of material within the collection that has LGBTQ value. It is often uncatalogued or acknowledged. I archived material on the Brixton Artist Collective’s Lesbian & Gay Artists Group for Tate Archive. It rapidly became clear that many items in their collection were invisible unless the short (searchable) catalogue included references to ‘Lesbian’, ‘Gay’ of other terms. Archivists work within cataloguing systems that are often unfriendly to LGBTQ concerns.

At a conference on alternative archives at Whitechapel Art Gallery in 2013 the Hall Carpenter’s Sue Donnelly explained the frustrations over time with national standard cataloguing practice. When she first arrived at the archive the single permitted cataloguing term was ‘Sexual Deviancy’. Things have improved but, for instance, as a result of the Brixton/Tate experience and Queer British Art, the Tate issued a text explaining the difficulties but also their adoption of an ISBN number to help draw out queer objects and resources. An ordinary member of the public will still find it difficult to access material unless an empathetic member of staff has a clear grasp of LGBTQ subject held.

So, in my opinion we do need a specific space that is able to collect, record and draw out our stories. One that is unafraid and out. A voice and safe space for our history. Many queer artists have work which museums refuse and galleries will not display outside the very limited LGBTQ friendly circuit. Much of it is important to our community but is in danger of loss – my own included. It is why I welcome Queer Britain, a project to establish a British centre of excellence. My partner and I collect work specifically in the hope that it will eventually find a home donated to such a space.