Mario Dubsky’s Spiky Garden

Mario Dubsky’s garden, like Derek Jarman’s after him, was his retreat. He told me he would rather be there than at private views or, as he described them, ‘amongst the shallow arse licking that pretends to be the art world’. Said vehemently in his usual provocative-mischievous manner, hoping to dare a response, it seemed a passionately held belief. But it wasn’t true. Mario could often be found at openings, not licking, but poking or kicking. He could be relied upon to say exactly what he thought of the work, not just to guests but to the artist’s face.

His garden was behind a four storied house in Archway, one of those slightly dilapidated Edwardian villas, with steps that go up to Ionic pillared porticos, from where you look down into what had been the basement servant entrance. This kind of house, built all across London, seem to soak up and reflect the neighbourhood they stand it. In today’s Pimlico they are pristine, with clipped bay trees quietly redolent of serious wealth, but once they were the drab grey tones of 50s Ealing comedies. In Notting Hill, they were once Colin MacInnes dereliction. Like a joint passed down the line they breathed-in with the canabish fumes of West Indian Windrush residents and exhaled with Bohemian psychedelic sixties survivors. The vibrant colours of both now give the houses their ‘green and yellow and pink and blue’, and all the colours of the rainbow.

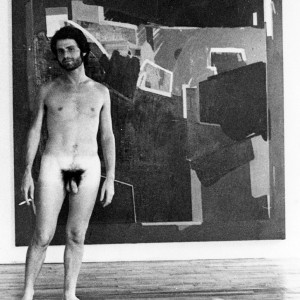

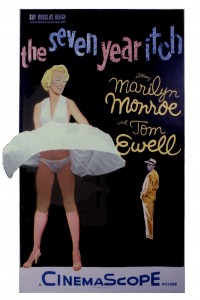

Mario’s house in Archway seemed somehow to reflect him: a corner of London yet to be rediscovered and uncertain that it would be. A dreary enclave when I first saw it, at the start of Thatcher’s Britain, with run down shops, a dole office and light industrial units set on a busy road junction. Number 12 St John’s Road was in a crescent of villas, mostly belonging to the Peabody estate, and mostly derelict or neglected. Curiously after Mario died my old art school, The Byam Shaw, moved into premises around the corner. The house will never warrant a blue plaque since Mario is destined to be a figure at the edge of accounts of other artists. He appears in the journals of Keith Vaughan and Derek Jarman for instance. Now occasionally noted as a member of the ‘school of David Bomberg’ (he never met him but bought work from Bomberg’s widow) he can be found in the catalogues of important sixties exhibitions like the Whitechapel ‘New Contemporaries’, hung along side big names like David Hockney. A moment of fashion celebrity came in a Sunday Times spread of bohemian swingers and shakers in big furry coats.

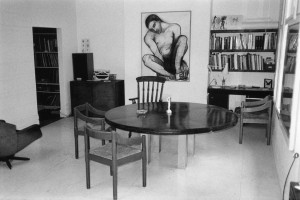

The interior of his house was a mixture of unfinished projects and alterations. The decoration, just as much as his paintings, were works in progress. The ground floor was one large studio. The first proper one I’d seen, it matched the romantic image I’d always had of artist’s spaces, but it was also a serious and practical place of work. I’ve learnt that one should always be suspicious of studios that are too comfortable or too decorated: such spaces are the homes of people playing at being artists; real artists play outside their studios. Professional artists have very functional, business-like spaces not those ‘shabby chic’ studios of so-called artists you see in lifestyle magazines. Even Francis Bacon had a kind of order, everything in its squalid place, one that reflected the messiness he saw in human lives and flesh. Things in studios work. They are not done for effect, or to decorate, or to create an image. The only comfort is usually in order to reflect on the work presently in hand; most often this is a comfortable but abused chair, possibly a kettle and perhaps a radio or some other source of music. Any apparent ornament is actually inspiration for more work and not ostentatious. This might include the ubiquitous postcards of other art, found objects, and often a mirror. Mirrors can be used to work directly from, or to reflect your work back to you, like another set of eyes.

Mario had a giant island work table on wheels spread with paint tubes and tubs. When I met him they were acrylic since he said he had developed an allergy to oils (I wonder now if it was not undiagnosed HIV related) with great pots and catering size tin cans packed with brushes, not pristine and carefully cleaned like a hobby painters, but abused and showing plenty of use. Ranged around on a series of easels were huge panels from his series of paintings representing the dark and the light sides of human endeavour. The title he told me was ‘An Eschatological Cycle’; I had to look the meaning up then, being only a student, but the end of the world was ranged in front of me. The Prophet of Doom an Einstein like figure in amongst cooling towers, threatening city sky scrapers and fighter planes were paired with the Mother of Invention cradling her child in a landscape dotted with telecommunications beacons, the space shuttle, and concord – things Mario thought of as white science as opposed to the dark uses they faced. Since I have always been a narrative artist, a dirty word in contemporary art, I was naturally amazed to see it so blatant in these pictures.

Mario took art seriously and was seriously well read. He thought work had to be tightly argued, not loose or woolly, and certainly not sentimental. I felt completely inadequate in the discussions we had, a silly boy who had no idea who Beckett was, could not quote passages in German or French novels, and who did not understand many of his arguments. The second floor of his house reflected this studious side of him. Reached via a staircase with no handrail: a plan to replace this with a giant organ pipe, salvaged from a derelict church, was unrealised just like the half finished wacky bathroom on the half landing. With its idiosyncratic shower sunken so low it was almost bath-like and lined with never finished mosaic tiles this was always impractical: probably partly designed with sex in mind I thought it proved impossibly awkward when he became ill with AIDS.

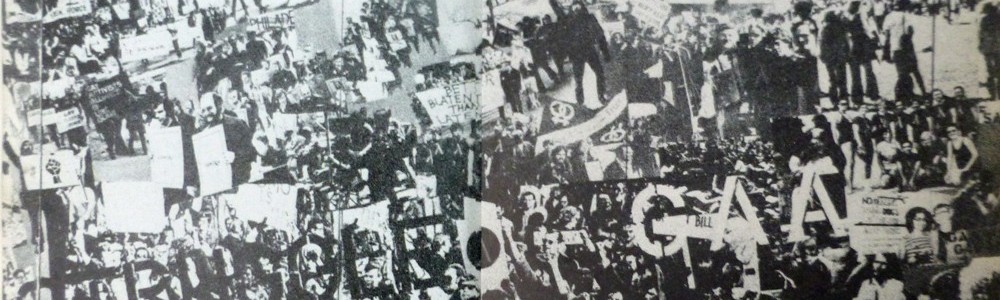

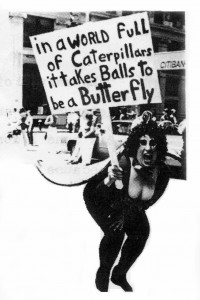

The first proper room on the upper floor was his kitchen, but really the whole floor was a carousel. Rotating from cook space, to the dinning room-come study, where books, art and food met, then on into the bedroom and back to the hall, but with no doors between any of them. He had spent time in the New York of the 1970s, the birth place of loft living and returning to London must have been one of the first to import the lifestyle. He brought back other elements of the lifestyle there as well; the politics of Stonewall changed his work from being semi abstract and decorous into something edgy and confrontational with made centre stage. The other liberating experience, found in backroom sex clubs like the infamous Mineshaft, the easy experimental sexual climate was probably when he became HIV positive. I always wondered, purely from curiosity, if it was the same virus that turned up when my own test proved positive. I always thought that Mario was both part of my gay family tree, and my artistic family tree with a like through him to Keith Vaughan, and in a way the virus was a part of that, like inheriting a gene.

To go back to the kitchen, it was one of those mildly unhygienic small spaces, possibly modelled on his mothers traditional Viennese one, that has a mysterious ability to produce fantastically delicious food. Dust covered half read books, on surfaces assembled from salvage, jostled a variety of interesting but chipped crockery. It was the first house I’d known where food wasn’t a chore, a workmanlike thing that had to be done to a timetable. I remember being particularly impressed by the coffee grinder to make fresh coffee on the stove: instant coffee was a luxury in my family home. Joining him for a meal with his mother when he served her trout, with the relish of a wicked smile having told me we would “have trout for an old trout”, was particularly memorable. There seemed not enough space to make anything much but, just as I found with Ossie Clark later, it never seemed to matter. If the coffee was fresh and the food almost medieval, simple things like fish with very fresh vegetables or a leg of lamb basted in honey, you didn’t need a lot of paraphernalia. If it came out a bit burnt the trick was not to apologies, talk and company were part of the seasoning that made it good anyway.

The study where meals were eaten was dominated by the huge round table that was actually a skip-salvaged antique top on the spool made for seriously heavy duty electric cable, both of which were also imports from American period. At the centre, usually alongside a vase of roses, was a large jar of home grown grass that he used to control his manic depression. He hated the proscribed lithium. A doctor friend, who came round to fuck pick-ups noisily in the attic room (he tried to with me but was so hugely endowered that, much to my regret now, I turned him down), would spot a manic period beginning and challenge him on whether he was taking it. Mario, slightly guiltily, replied saying that he had his best ideas on the highs and deliberately allowed his dosing to slip. The lows were another matter entirely. Against the walls around the table were bookshelves, Indian miniatures, hisown work and several really fine pieces by other artists, some friends others he admired. Artists make friends with the dead and the living so these included a drawing by David Hockney who he new, an early Vortisist period David Bomberg who had been a strong influence on his own work when he was the youngest student to be accepted at the Slade. Bought fairly cheaply direct from Bomberg’s widow, this later sold for £50,000, helping to pay Mario’s death duties. His Sister Barbara managed to hold onto a particularly beautiful nude bather by his close friend Keith Vaughan, who incidentally Mario thought had been another victim of manic depression.

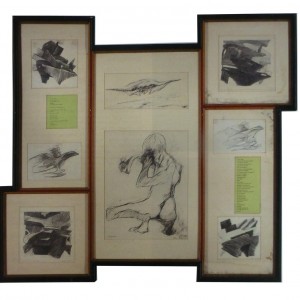

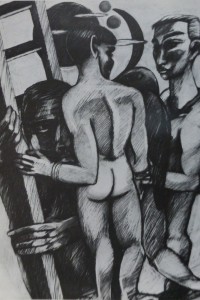

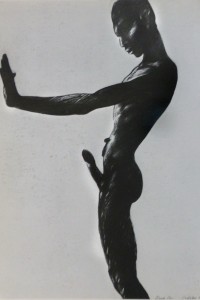

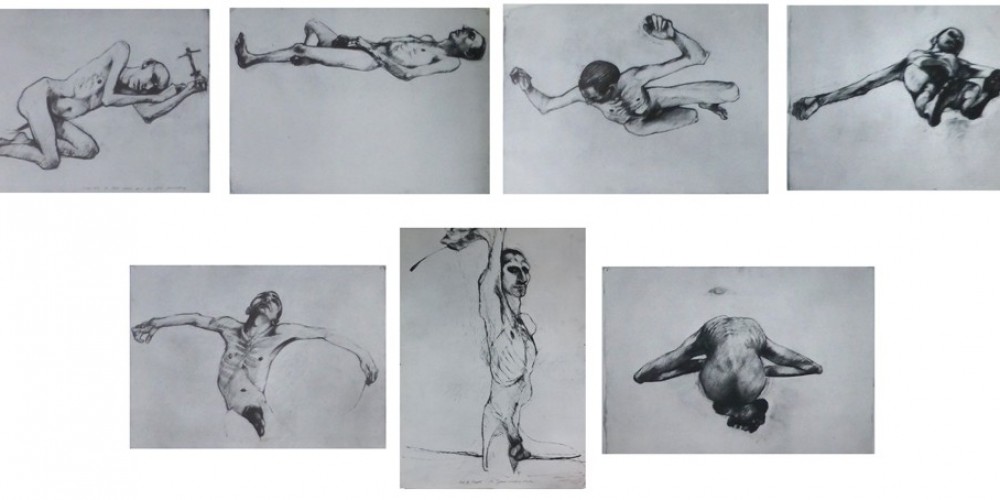

The bedroom was economically furnished. Not in a monetary sense; nor do I mean it was minimal in the decorator’s sense. It just had enough furniture to serve and plenty of spaces to spread out. This was because it doubled as a second studio in which to work on drawings. These are both his lasting triumph and were to proved his curse. Their rigorous whittled figures, made bone-like, bleached of any fleshy voluptuousness, meant that they were admired but not loved. I thought they were wonderful: tough like sinews and muscles on a man doing hard work on a frugal diet. The wasted figures of his pilgrim series had truth but were so angular and violent-seeming that they provoked disquiet. Reviewers said it was an existentialist distillation of the Jewish holocaust (as art critics tend to). As usual they missed the signifiers that degenerates, and other people who do not fit, had worn in the camps. In one of his paintings ‘In the Hold’ all the slaves in the belly of a ship-like prison wear pink bangles. In New York he helped make a mural for the Gay Alliance Fire House and if you Google his name now this, and a painting the Tate reluctantly accepted as a gift from his sister, is what will tern up. But he was also interested, well ahead of most artists, in what is now called the Green agenda. His real ongoing theme was man’s reckless abuse of the environment and of beauty. In the drawings’ titles, ones like ‘Man Amongst the Symbols of Nature Alarmed’, he made clear his belief that a person adrift from philosophy and history, living for the moment, was in love with false beauty and endangering nature.

Living for the moment, ironically for Mario as it turned out, was the very thing many gay men with AIDS were condemned for. He visited the carefree, throwaway sexual culture, observed it and, after dissecting it in his work, never ceased to condemn it. Not just in sex but generally, he felt modern man failed to create or build, but only consumed. His figures eat where there is no nourishment and become thin, but go back for more. I think really great art has the ability to predict: as if by letting go of yourself, but holding onto craft, you channel, like a medium, more than your own concerns. Looking at them after he died these etiolated figures foreshadowed the wasting of AIDS but there was something more than that. They look as if he has whittled away at a fleshy idol of modern life, peeled back the fat of indulgence to show the core archetype under the mask of modern. That figure was monk-like and spiritual because of what he gave up, because of what he had experienced, not because he had abstained or avoided it.

I wanted very much to be drawn by Mario. I would sit naked on the bedroom floor after sex, curled into what I hoped were interesting poses, pretending to read a book whilst all the while hoping he would take the soft black six B pencils that he used, that most people mistake for charcoal once on paper, and capture me. He never did this at the time, but I think he did draw me in the end. In the two years after we met, just before he became one of the single figure statistics of the plague counter, a series of figures which were unlike the others appeared. Contemplative Narcissi, rounded and young, curled in on themselves; I thought I saw myself in them, seen from where he was standing. He was a cynical man, quite embittered that few people understood his move from abstraction to figuration. Seen as betrayal of progressive modernist concerns, a retreat into narrative, a cardinal sin in an art world increasingly drawn to conceptual work, along with what a homophobic academic establishment saw as his apparently queer morality, meant he was dropped as a one of the ‘in’ talents. His garden was not really where he turned his back on them, but where it didn’t matter that they had turned away from him. But the cynicism had older roots than that and was also self-defensive on an emotional level. Robert Medley once told me of the closeted Mario, the serious talented student he had taught at the Slade, the youngest student ever admitted, had been very insecure in his sexuality. His fearless, nastily witty, lashing tongue was a defence as well as a jousting tool. It was in New York that Mario ceased to be embarrassed about who he fucked-with in every sense of the word but I thought he was lonely man when I met him ( something Barbara later confirmed from his diaries).

A big love – there is always one – called Steve, had moved on. He showed me a card from him posted in Italy: “Having a great time with an Italian whose arse you can move the kitchen sink into – XX Steve”. He laughed but I think it hurt. Barbara said I had left more of a mark than he ever led me to believe and that he loved me. I’m not sure if she was simply wishing he had had some comfort or if she knew something I didn’t. Love is a strange idea I think. A blackmail in a way, the ransom reassurance. I think Mario would have said: “it is usually a sentimental construct”. I’d rather say someone is important: they matter and they take space in my head that I gladly give up. You keep them there even when they are gone and you guard them. If that is love then I loved Mario. I don’t myself think that I made much of a mark emotionally on him.

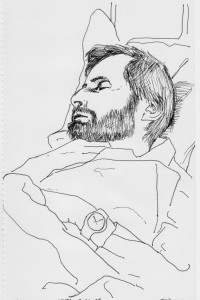

Certainly he never said anything very encouraging about my work. He was surprised by my Hockney-esque pen drawings though, his – for once – gentle good humoured single criticism being that I had lingered rather too much on the groin area of nudes . (He was right: unlike Hockney, who usually over caresses bums, stroking them with his crayon, I’ve always been a cock and face man). One of these drawings was done sitting by his bed the night before he died. The first person I knew who died from AIDS but also the first person I had shared the nearing death moments. He could not speak but made small noises of distress so I touch his hand with my left and drew him with my right.

He taught me about sex though. Always direct he made me read about STDs and gave me helpful hints: “you don’t have to lie there like a piece of meat you know?” Surprising how many men don’t try to improve their technique by talking about it but Mario was too direct to let it pass. A year later I came to see him, we had sex and I took huge pleasure in his wryly delivered “well – haven’t you changed!” It was then that he asked me if I wanted to come and live in his attic room. I was to be his assistant and, as he put it, “we could have sex now and then”. By a curious twist of fate I had had two other offers of partnership at the same time. Another artist was one. A Scotsman called Gerry, a recovering alcoholic with a fetish for white socks and trainers, and one of the nicest and most Zen centred people I’ve ever met. The other was Richard the partner with whom I’ve stayed for 26 years. Mario would have sharpened my artistic pencil faster than I did on my own, but at the time I needed tender care not the harsh pruning he offered.

We talked about art of course. I liked the Rainer Fetting shower pictures at the ‘New Spirit in Painting’ show, but he showed me Beckman, explaining how much tougher and authentic they were; he drew his homoerotic version of Beckman’s ‘Argonauts’ after that conversation. I found a book in his library of erotic Pompeian art and was astounded at an extraordinary bronze tripod table, its legs cast as ithyphallic satyrs. He drew a version called ‘Black Pan’ after that, mimicking the curious reflexive pose, like Harlem ballet dancers, of the figures in profile bending away as they stand hard and taught. Neither were great drawings but he thought, I think, that the sexuality needed to be restated: by putting it in parenthesise he said ‘don’t you see this? You cannot ignore it’. In return for his introduction to a serious approach to art I worked on his garden. He wasn’t a knowledgeable gardener and, taught by my mother, this was something I could offer in return.

Reached via steps leading out of the ground floor studio, his small but witty retreat, took up the part of the space behind the house not occupied by the sunken portion belonging to the rented-out basement flat. Right at the back, below a row of lime trees, half hidden by ivy, a plaster cast of an Aztec god salvaged from a skip at St Martin’s School of art when they threw out the accoutrements of the academic life room I’ve always thought South American artefacts are like their obsidian knives: miraculously crafted and totemic, but with a dark soul. In putting it there his unfashionable salvaged pagan god, watched visitors like a malevolent gnome.

Like his pictures an unsettling focal point. The plants, at least in my memory, reflected him too. Angular pointed metaphors for Mario’s own somewhat sharp presence, that is prickly and difficult, but beautiful when seen in the right light. Things like spiky Eryngium and Mahonia along with poisonous Euphorbia. Bleeding pure white sticky cum-like sap if you bruise them it can blind you if you get it in your eyes. Most of these plants had been there when he arrived along with the ubiquitous London Buddleia, coloniser of bomb sites and dereliction. His form of gardening was perversely to kill off anything that was there, or arrived, which he thought redolent of an English cottage garden, anything suburban like bedding plants, the mundane or boring easy colour, did not stand a chance. Except for the roses: viscous old varieties, but with spectacular blooms and scent. In amongst them were Mario’s cannabis plants. Not a planting combination the RHS would have approved but actually quite an affective mixture. The roses were stolen from the other derelict gardens in the street and I was set to work digging up more. Close to the house, screening the basement flat’s patio, was a rectangular pond backed with bamboo. At one end submerged in the water was a fibreglass head and shoulder bust of a swimmer, looking as if he was taking a bath amongst lily pads. There were other plants as well: Madonna lilies and Crocosmia (he would have like Crocosmia Lucifer) and I think the climber on the house was a Wisteria.

Usually at Camberwell or the Royal College degree shows you could guarantee Mario would be sitting in the space of the most original or difficult student, certainly not in with VIP guests. On one occasion he delighted in sitting amongst a female student’s pictures of giant fanged cunts. On another he spent the evening telling people visiting a resolutely straight-acting male student’s work that it would only really become good when he admitted he was bisexual. After my initial period of staying with Mario I saw him intermittently at private views and gay pubs. I was the target on several occasions for his wrecking ball, mostly demolitions for pretentiousness. On one occasion during my period as a New Romantic, when I tried to create an impression by dressing outrageously, covered in leather & studs, with teased hair and mascara, he came across me in the Salisbury pub. He delightedly stripped me bare verbally, told me the pursuit of mere exhibitionism would ruin me as an artist, and humiliated me. I was furious returning home to write venomously about him. He was right though and if it hadn’t been for him I would never have produced anything but egotistical nonsense. One of the phrases he taught me is the derogatory “ego stroking” – something he never did.

My worst experience was when he came to my Diploma show at Byam Shaw where, despite my passing with a distinction, he deftly slashed almost everything on show. Designed to shock it was full of deliberately provocative and sexual themes but he hated what he called my “me, me! look at me!” art. Ridiculing all but one painting as inept he demanded to see my almost non- existent drawings. The one piece that he grudgingly said was quite well done but lacked bite (“satire must have teeth, razor sharp if possible, in order to draw blood”) had taken me months to make and involved sound and a wind machine. I was devastated and fled in tears. Mario revelled in his self appointed role of dark fairy prophesising at Sleeping Beauty’s ball. He saw it as his duty to say what he thought, however painful it might seem. In the end I’m glad I pricked my finger on his poison spinning wheel gift. It woke me up and made a better artist … after several wounds.

To be fair he did not expect dialogue to be one way and solicited views on his own work. Personally although I had views on it I thought it would be almost impudent to offer them to him, expecting only pity for my feeble attempt. This is actually exactly what happened when I did give my assessment of his work when he complained I hadn’t after his 1984 retrospective. My opinion, for what it is worth, is much the same now as it was then. Bright colour and, to a lesser degree, paint were never his natural materials. Only when he put his palette into the earth did paint, oil rather than acrylic, work well for him. Sack cloth and ashes. He was a truly gifted draftsman though and his archetypal imagery has a potent and ancient feel. His best work is to be found in archaic darkness.

His earliest work, as every student’s work is, was derivative. It is a pity that he so often ends up roped in on account of it to the ‘School of Bomberg’. Even then in those early pictures there were the stirrings of buried forms and eyes in geological slabs of thick painterly darkness. The geology diverted briefly, during his most commercially successful period of painting, into a strata of brighter deco-like beds of colour. The remains of ancient cultures under a Mediterranean sun.

The darkness returned about the same time he became politically active in the Gay Rights Movement immediately after stonewall. A pessimistic storm moves under tectonic plates, obsidian shards, like the remains of shattered black glass mirrors. Recognisable form was never far from the surface and soon rose up in these ‘black’ paintings and drawings, his “inchoate mass spectres”. Gradually these formed into strange amalgamations of ruin and geology: what he called ‘natural history remains’. There always seemed to be cave-like empty eyes watching from between the layered strata and soon creatures, curious primitive men and women, began to crawl out of the primordial spaces between.

Mostly Adams rather than Eve’s, they were bony and dark, like foals trying to stand on shaky feet, but often deformed, half morphing into spanners or aeroplane wings, animal bones or set squares. Progressively emerging during the 1970s I find it hard not to equate them with the emerging Gay Liberation movement. Like Palaeozoic era creatures crawling onto dry land they began to move about examining things. They divided into two tribes, the Satyrs and the Pilgrims. The one a brooding dark presence of nature, waiting always; the others, hermit-like, slept, dreamt, floated and puzzled at where they had washed up. In Mario’s spiky garden these etiolated figures were the sacred and the profane reversed. The holy men sit in clearings penitent but unable to connect with nature which protects itself, arms itself, and waits with ominous foreboding and retribution off the path.

These drawings are claimed by turns to be gay art, a concept Mario denied and thought stupid, or memories of the Holocaust. Like most troublesome art they are more complex than that, more individual. He was a mixture of baptised Slavic and Jewish and his family had lived in the Vienna of Freud (he affectionately described his mother as a ‘cleverly disguised monster’ but was proud of his ancestry). A child of the ‘60s he woke up to politics and sex in the agit-prop world of New York: of feminism, Vietnam and Stonewall. Technology is often not a force for good in Mario’s work, but an ill used tool. ….His late drawings, which have been called perverse, or homosexually obsessive, are actually direct criticism of hedonism and exploitation. These figures are wretched because they do not belong, because they have become detached from nourishment after devouring everything like mindless locusts. Looking at them now, two predictive themes seem to stare out. Man devouring nature till cursed by it, or pursuing a self indulgent pilgrimage via sex to unchain himself from the idea of sin.

Mario’s funeral was of course a humanist service and he is buried appropriately near Carl Marx. His saints and sinners are metaphorical. He told me once that the bible should be banned for two hundred years so that we could then read it as wonderful mythic literature, not as a moral code from God. His outrage at the Gay News blasphemy trial produced a series of figures called ‘Tom Pilgrim’s Progress’ drawn from Tom Dawson a model at Camberwell School of Art. Created as an alternate pilgrim this austere gaunt creature appears to have been abused by faith – prisoners of it – desiccated by its lack of joy. One foetal figure, with a cane thrust in his rectum, grips a crucifix. Another ‘Saint’ ejects a Christ-like spectral nude from his arse. A portrait head, deliberately echoing the painted pious profiles of renaissance church donors, pictures a sad faced man, shaven headed with a cross suspended from his earring but with a chain around his neck. Figures like him, but pumped up by steroids and fettered by chains only when they wants to be, is a stock character now in gay clubs. The ‘circuit party’ lifestyle is deflated in Mario’s penitent sinners; it as if he shows what is within the fleshy fruits. The real problem with mono-judgements about artist themes is that it locks-down meaning. Mario felt ugliness bred in dark restrictive places. His is a complex cocktail of references. Jewish references of course, but he reinserted those that put him into the pink triangle wearing camp as well. He is critical of Man in general, a mindless mass chewing up a world for greed. His figures are individuals, not gangs, not majorities, not average classical ideals, gay or otherwise. He was for instance adamant that there was no such thing as ‘Gay Art’. In conversation with Emmanuel Cooper about the subject at the ICA not long before he died, he told the audience that artist could be gay but art wasn’t gendered. Agit-Prop, like the Firehouse mural made with John Button, was an entirely different animal he said. I don’t agree myself: artists get into their work like the fossils he studied got into his. The Science and Natural History museums, his garden, ancient Greece and the Mineshaft all contributed to what he made and it is a queer vision.

Far from being welcomed in the queer comunity, these drawings were not popular with gay men when they were published, in the first art book issued by the Gay Men’s Press. They were not the hedonistic figures of the disco or beach. They mystified both an art world focused on the conceptual and a gay one focused on hedonism. Now they look like the warnings of an unheeded prophet, linking the corruption of a worn out morality to a parallel abuse, as he saw it, of nature and self respect. He saw the same arrogance behind the artificial ‘natural order’ that gave rise to the death camps, unchecked science and the brave new world worshiping false gods. Dolly the sheep would have been a perfect sacrificial lamb for Mario. The metaphors for ecological rape that he was feeling for are now a common-place.

Like a fastidiously manicured diminutive satyr, his wicked eye is still looking over my shoulder, pointing out failings and giving me a kick with a cloven hoof, when an easy solution is sought. Several mythic beasts are guardians in my own garden now. His house deserves a least a minority plaque which might read ‘Mario Dubsky, humanist artist, gay activist & perverse gardener lived here’. Mario usually had the last word in life and his own epitaph, had he the choice, might have been taken from the header of his notepaper.