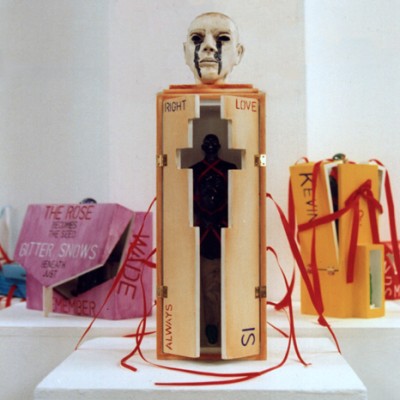

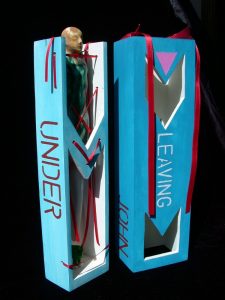

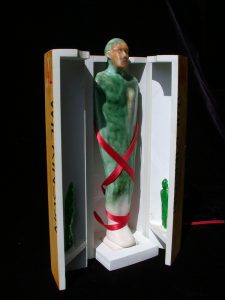

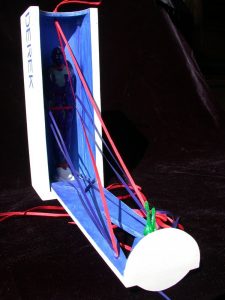

Seed Boxes

“the life of the dead consists in being

present in the minds of the living”

(Cicero)

The most difficult task in trying to show to people little affected by HIV what it is like to have your life turned upside down by it, is trying to convey multiple bereavement. Numbers do not help: they simply compound the problem by depersonalising individuals. Saying I had lost x number of people does not begin to describe the effect it has, the feelings of being the only survivor of an endangered species. The now ubiquitous mobile phone and digital camera means photos are out there but with many of these guys too late you realise you don’t have anything, or maybe only a funeral or memorial card to recall them. I wanted to give my friends form so that the numbers would mean something.

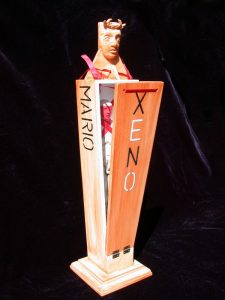

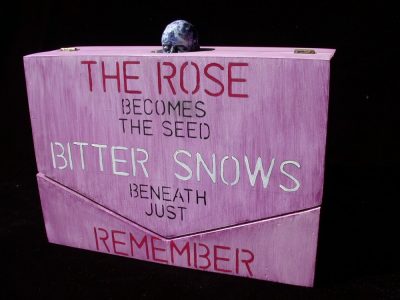

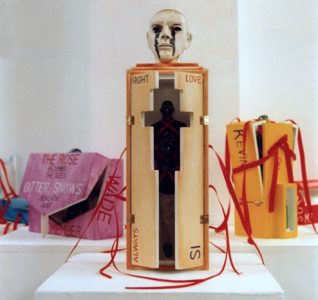

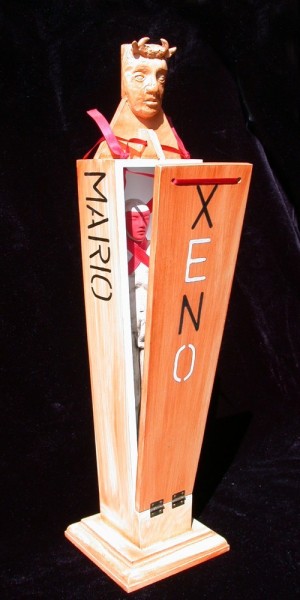

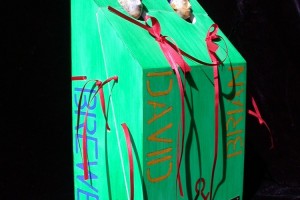

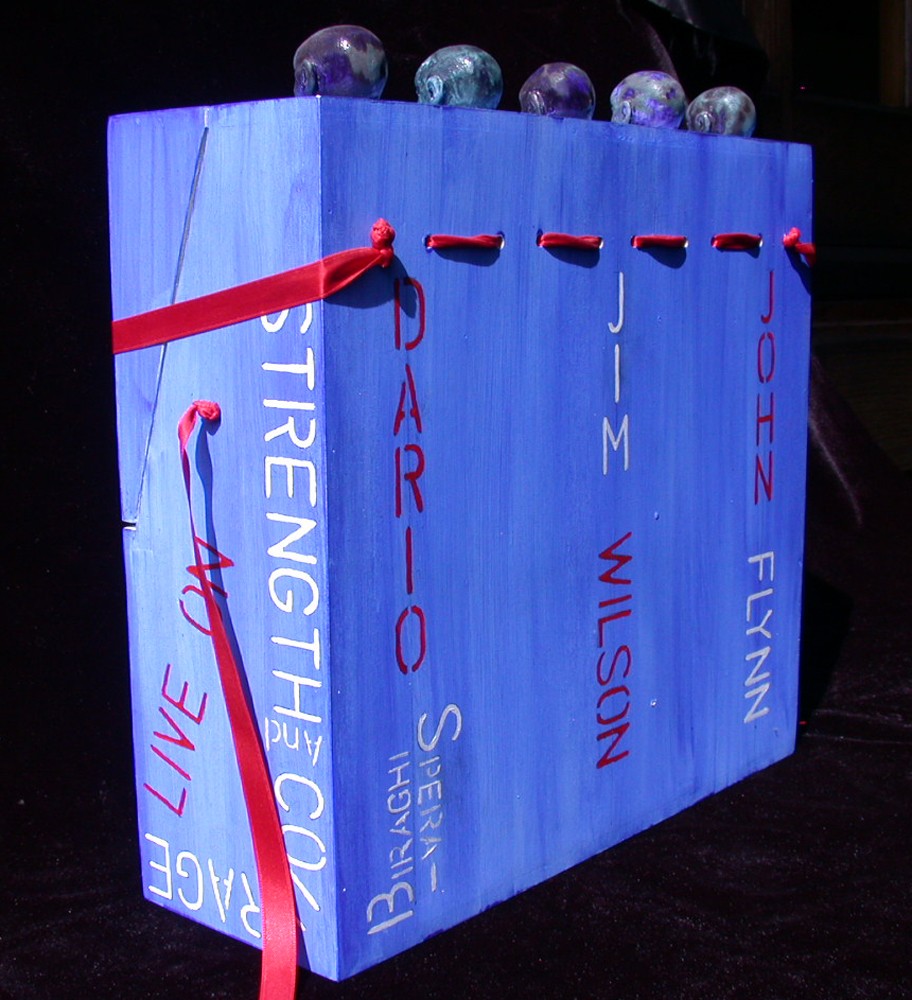

In the end I made these boxes containing ceramic figures like those made for Egyptian tombs as totems for each person, their names painted on the outside with text which I hope evokes them. Each box also contains a ‘seed’ figure because I feel that memory preserves life in some way and they continue to grow.

The boxes were first shown in my Unstill Lives exhibition but they are not made as art works. I made them for me and they are not for sale. They were shown again as part of Norfolk open studios event an garnered some press attention. In the end these works come down to being a witness, through them I leave some trace, an echo or a dim reflection of my experience and of my friends, that in some small way defeats the efforts of the virus to destroy them.

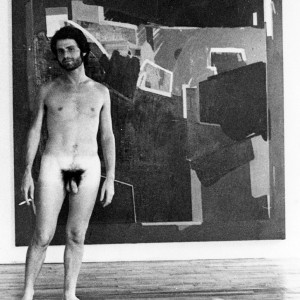

Mario Dubsky 1939 - 1985

Sketchbook entry: October 1995

…..At the back below a row of trees a plaster cast of an Aztec god, half hidden by ivy, watched his house. Mario had salvaged it from a skip at St.Martin’s School of Art when they threw out the accoutrements of the academic life room. In many ways this reflected his work and explains why he was a misfit in the art of his time: he salvaged pagan gods from unthinking hands. The plants, at least in my memory, reflected him too. Prickly and difficult but beautiful when seen in the right light. The roses most of all – vicious but with spectacular blooms and scent…..

…..Mario revelled in his self-appointed role of dark fairy at Cinderella’s ball, but saw it as a duty to say what he thought, however painful it might seem. His gift was like Cinderella’s spinning wheel but in the end I’m glad I pricked my finger…..

…..Like a fastidiously manicured diminutive satyr, his wicked eye is still looking over my shoulder, pointing out failings and giving me a kick with a cloven hoof, when an easy solution is sought. My last word on him must lie with his note-paper decorated with a drag queen holding a placard which reads, “In a world full of caterpillars it takes balls to be a butterfly!”.

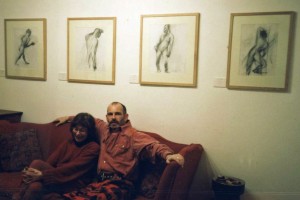

Mario has a larger entry here but I’d like to record his sister Barbara Dubsky who worked so hard to keep his work in view despite here own health problems. Here we are at the Boundary Gallery where several exhibitions were held of his work.

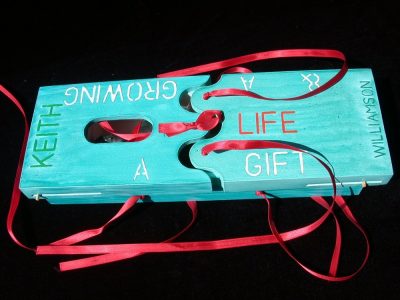

Keith Williamson

Sketchbook entry: 11 January 1993

Keith died just into the new year. This unassuming bear of a man spent the last 3 years as the mainstay of Body Positive London. I met him at the HIV swimming group where he was trying, not very successfully, to learn to swim. He encouraged me to join BP as a volunteer on the Helpline. Such a kind, gentle man with a sense of humour which was like he was: gentle, never malicious.

I last saw him at the Helpline Christmas party. He looked tired and a little gaunt but not dangerously so. He spent the evening putting people at ease, effecting introductions and, along with his partner Barry, tried to see that everyone had a good time. Before we sat down to our meal he asked for a minute’s silence for those who were no longer with us, volunteers who had died, and afterwards during the meal Auld Lang Syne was played, and for me at least took on a significance it has never had before.

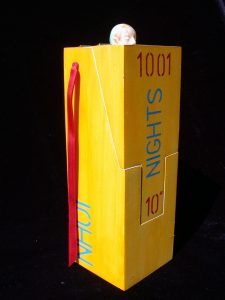

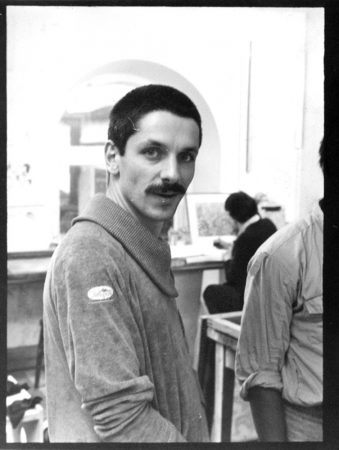

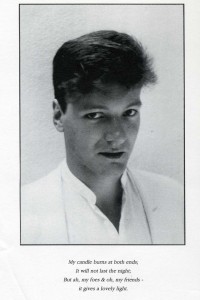

Nick Balaban

Nick Balaban was, in the words of his favourite song, ‘the man with the child in his eyes’. Beautiful Turkish eyes inherited from his father that made people ask if he was stoned. I was at art college with him and he was Matisse to my Picasso: colour and joy of life personified. Sure the child could throw some tantrums and suck his thumb, but he was the most natural person I’ve ever know, never thrown by who anyone was, he just was himself. Nick was the partner of dress designer Ossie Clark. They were together as long as Ossie had been with his wife and yet Ossie’s obituaries neglected to mention him. When Ossie’s diaries were published and not a single picture of him was included I was so angry; at least I got to change his Wiki entry to write him back in to the picture. I could have kissed Marianne Faithful for mentioning him in the South Bank documentary about Ossie.

Sketch book entry: Friday 21st January 1994

I’ve been putting off writing about Nick’s death on January 3rd at 11.30am. I’m finding work very much a struggle and strangely lethargic: an apathy of purpose consumes me. Nick’s death seems unreal, after all the traumas of the last three and a half months while he was in hospital suddenly there is only an absence, a silence.

The night before he died I sat with him for about an hour. I told him I was going and would be back next morning. Even though he had appeared asleep during the whole visit he tried to say goodbye, but all that came out were inarticulate noises in the back of his throat with his mouth shut (now I wish I had tried more to understand). Next morning I arrived at 11.30 the nurses said nothing as I past their station. On entering Nick’s room I found Molly, his Mother standing over Nick and a young man I didn’t recognise standing slightly back. At first I thought Molly was wiping Nick’s mouth after he had been sick so I stepped back out of the room a moment. Then it occurred to me she hadn’t noticed me come in so I should let her know I was there if she needed help. I went back in. The scene was unchanged. Molly was touching Nick extraordinarily gently stroking his face and hands. I suddenly realised the young mans hands were in an attitude of prayer and flush of adrenaline and panic hit me. I know now what it feels to be a cliché: my heart was suddenly heavy, a dead weight materialised in my gut, and I felt the colour drain out of me. Nick’s face was looking up towards the ceiling his eyes wide, his mouth a little open.

I retreated from the room and wanting to know if I was right in thinking he had died, I went to the nurses station and said “I think Nick’s just died”. The nurse replied “It’s quite possible”.

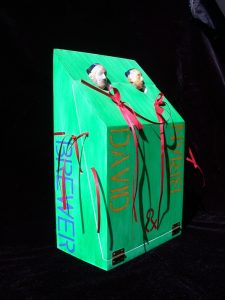

Brian Reaper & David Brewer, 1960 - 1995 & 1963 - 1991

Sketchbook entry: 25 September 1995

Brian Reaper’s funeral today, two years after David his partner. Stewart, Kacz, John and I when to the pub to toast him farewell. Although the occasion was fairly jolly I couldn’t help but notice two things. Firstly, there are so few friends still alive, who knew both us and Brian, that we learned of his death from the barber in Earl’s Court. Secondly, Stewart sitting on a bar stool, resigned to his increasingly debilitating illness, reminded me of Nick the last couple of times we went there. His arms are covered with needle bruises where the nurses have mucked up finding veins for his drips. He has the same strange air of matter-of-fact, almost subconscious, acceptance of his physical limitations, as if he is not using up the energy he needs simply to get through the day in an unnecessary fight against the inevitable. With Nick I fought against this, thinking it was a giving in. I’m trying not do this again, trying to respect Stewart’s choices rather than my own solutions. Obviously I talk to him to try and find out what he is feeling below the surface, but I try not to judge by my own values this time. Will he see the summer?

Eddie Surman 1975 - 1996

Sketchbook entry: 18 March 1996

Returned from a weekend in Suffolk to find a message from Peter on the answering machine saying his boyfriend is dead. Eddie was a sweet, quiet boy though I did not know him well. Bright eyes, cute and intelligent, he and Peter were a couple you could take hope from. Both positive but deeply in love, Peter at 41 twenty years older than Eddie, but a perfect match. They had been together for about eighteen months and each spoke about the other as the light of his life. Proof that diagnosis did not mean life was at an end. Eddie took his own life.

Carefully preparing beforehand to avoid Peter knowing anything or being implicated, he took a massive overdose. He would have been twenty-one two days afterwards. A note to Peter explained that he could not face Peter becoming unwell or that he himself should die slowly and become a burden. No one had the slightest idea that this was on his mind other than that he had been frightened by Peter’s recent hospitalisation with P.C.P. The pain and turmoil behind those sparkling eyes, hidden from the world and even those dearest to him, is incomprehensible.

Some like Eddie make the choice that their life is over, that going on is too painful. Who is to say that this is failure? To be able to make that difficult decision, that you wish your life to stop because you know with certainty that the future will not improve on the past and you choose to deny fate the chance to inflict pain, takes a particular courage.

For those of us who keep hope alive that another day will bring meaning, or that something we do will give purpose to life after loss, there is no respite. Every day another name is added to the list. In the end we all weigh life in the scales hoping that they will tilt in our favour.

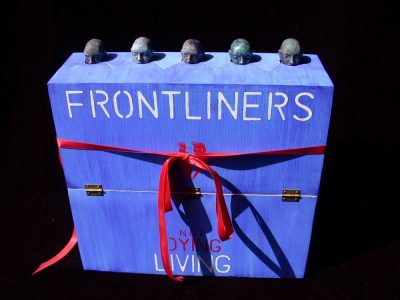

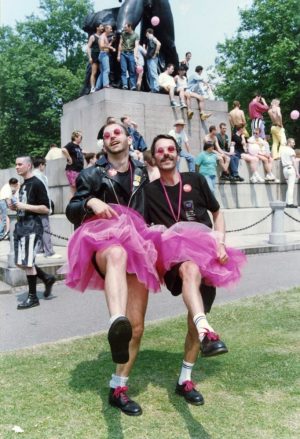

The Frontliners

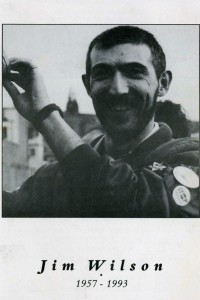

Frontliners were a charity composed of volunteers who were themselves diagnosed with AIDS (you couldn’t become a member if you weren’t). I first came across them when I trained as a Buddy, a person who supported someone with HIV/AIDS trained by The Terrence Higgins Trust. Jim Wilson took the session on the training course to give the perspective of a person with AIDS. He had been a Royal Protection Police officer and was remarkably no nonsence and full of humour. I recall him saying “don’t think just because someone has AIDS they will be saintly: if they were a shit before they are quite likely to be an even bigger one now!”

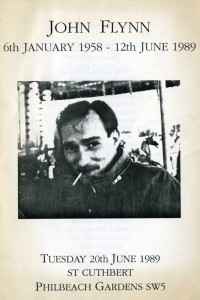

I became a Buddy to Stewart Duggan, a Frontliner based at old Chelsea & Westminster & Chelsea Hospital (or the Royal WC as it became known). He insisted I met him in the office and was interviewed for my suitability in front of John Flynn and Dario Biragai (and irish John). All had had wicked tongues. Tripping over a fire bucket as I went in Dario said “kicking the bucket so soon dear?”. Dario was famous from his time as the coat check ‘girl’ at heaven and nearly all the others had once been barboys there, donning tight red disco shorts in the Star Bar. Stewart became one of my closest friends in the end.