Bill Ward (1927-1996)

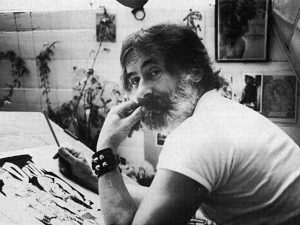

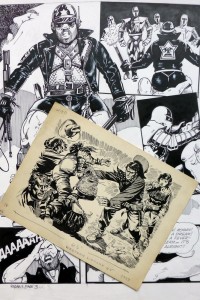

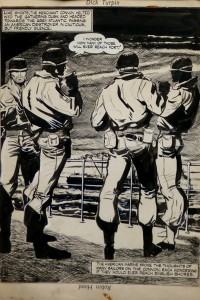

On 24th July 1996, at the tail end of the worst period of the AIDS epidemic, the British erotic graphic artist Bill Ward died at Stratford in London. Not to be confused with the American heterosexual erotic artist by the same name (William Hess Ward 1919-1998), Bill was a gay graphic artist born 20th August 1927 in East London. His publishing career began as a copyboy in newspaper publishing before becoming an art editor for children’s comics and then a graphic artist. He worked as a graphic artist for Amalgamated Press and Fleetway on childrens’ comics, notably their Thriller series (November 1951 – May 1963). In 1957 Bill had his first erotic drawings published anonymously in the British physique magazine Male Classics and he would later work openly for hard-core American magazines. Bill’s work features in the same issue of Drummer that includes Robert Mapplethorpe’s first commissioned cover (issue 24, September 1978).

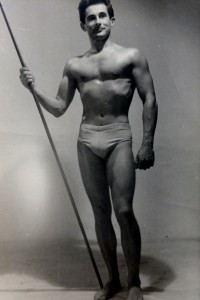

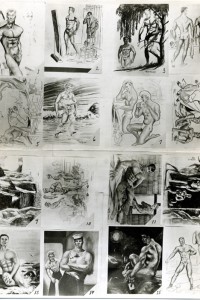

Censorship in the early days when Bill was working as an erotic artist dictated specific working methods. It was illegal to have gay sex and this impacted on the ways in which erotic drawings could be reproduced and circulated. The more usual methods of reproducing drawings, for example as lithographs or etchings, were problematic because this would have meant gaining access to printing presses operated by people who were gay – or risk being arrested. Similarly, photographers working with gay subject matter had to develop and print their own photographs. In order to be able to distribute gay erotic drawings they were marketed in the form of photographs (hand printed silver gelatine prints) made from hand drawn illustrations. Catalogues were made to market these photographs – for which the photographs of illustrations were re-photographed. Frequently illustrators used pseudonyms to protect their identities.

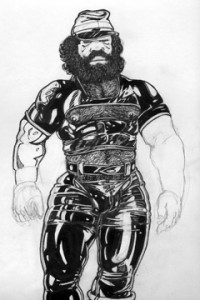

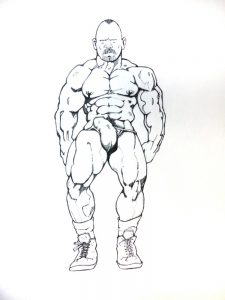

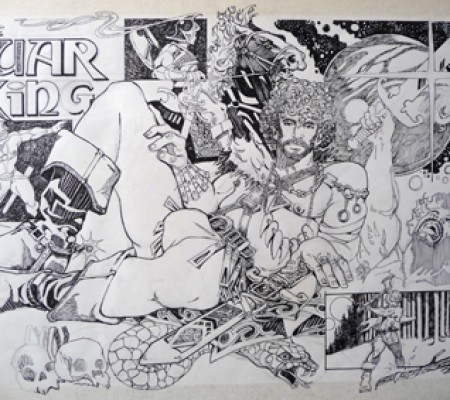

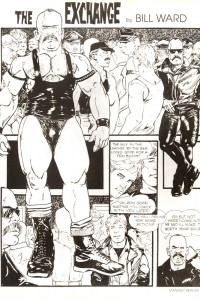

In November 1996 Bill’s partner, the silver expert Stephen Helliwell, also died. Bill’s ‘dowager’ boyfriend, the actor Brian Rawlinson (1931-2000), owned an outhouse piled high with debris where Bill had once worked. Later in life Bill had attracted a fanatical following, as ardent as that of Tom of Finland, for his exquisitely drawn large hairy men (bears). A counter point to Tom’s perfect physiques, his often large-bellied characters indulged in explicit urban and Sci-Fi adventures that echo his mainstream comic work on stories such as Dick Turpin. Brian looked on it affectionately but was not interested in and did not have the time to find a home for the material he had been left.

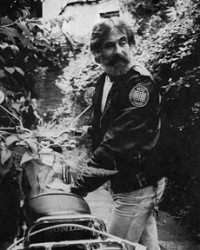

Bill had belonged to a British gay bikers club called MSC London, to which I and my friend Robert Bremner also belonged. Robert modelled for ‘The Adventures of Drum,’ one of Bill’s best-known characters. Sometime after Bill’s death Robert heard that Brian needed to clear the studio in order to rent it out. Not knowing what to do with 100s of pornographic magazines and accumulated detritus including Bill’s explicit drawings, he felt he had no option but to throw the bulk of the material away. Robert asked me to help mount a rescue in case material could be saved. He knew I had been involved with the consolidation of studios of two other casualties of AIDS with problematic gay content: Mario Dubsky (1939-85) and Nicholas Balaban (1955-1994).

Collections are often too quickly disposed of either by family that reject material that is provocative or offensive in favour of that which has sentimental value or by galleries and institutions cherry picking on current agenda. Much of the rest ends up, at worst, thrown away, at best, for sale on eBay. The personal photograph albums of, for example, Jared French (1905-1988) and Paul Cadmus (1904-1999), pioneers of homophile subjects and members of the PaJaMa group of photographers, have been dismembered in this way. Potentially important private albums too are lost or slumber falling into decrepitude for want of a plan or the knowledge to conserve them (the personal effects and artwork of Sam Steward for instance were slowly disintegrating before found by the writer Justin Spring).

We visited Brian just in time. The studio was to be dismantled and the contents thrown away in a matter of days. Brian gladly gave us permision to take anything we thought appropriate but we had only one day to do so. We promised to try to get his work seen and to conserve it. Bill had worked in one corner of what was once a coach house but not for some time. The stored junk and chaotic piled magazines (mostly Drummer, Him and Zipper) had to be sifted to find work. With my previous experience, and a writer about antiques and an activist involved with archival research into LGBTQ art, I know that it is often the related material that can help tell a story. If lost, a history can be lost too. As well as many exquisite drawings (including some relating to his earlier career as a children’s illustrator) we rescued 260 individual vintage physique era photographs, including an album of Bill’s dating to the late 1950s and related printed marketing material used by many little known gay British photographers (both British and American photographers are represented, but the British examples are less known).

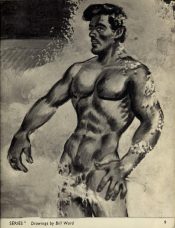

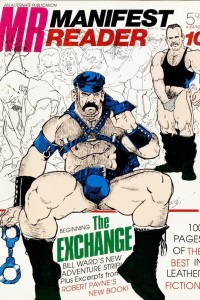

Related ephemera included discrete mail order catalogues distributed through publication and advertisements in Physique era photography magazines read by gay men. A number of images were of Bill himself, an ex-merchant seaman, proudly posing. Carefully examining the illustrator catalogues put out by some of these photography studios, led me to conclude that (whilst he was still working for associated press and needing to be cautious) Bill made works under the pseudonyms ‘Titan’ and ‘Tristano’ (a version of the last image above right, published in 1957, found in the studio has initials ‘BW’). The archive contains many original drawings and sketches (1953-1996) and original commercial work (1953-1996); accounts, and correspondence; 18 scrap books containing pasted-in source material. We could not keep all the magazines but removed pages with his published graphics. These included British publications such as Him, Sam, and Daddy as well as Manifest Reader, Stroke and Drummer in America where he became very well known. The famously illusive legendary artist Rex owns work by Ward and made a point of getting to know him.

Gay men have frequently supported each other via what was once disparagingly called (in Section 28, UK Local Government Act 1988) ‘pretend families’; a web of mutually beneficial contacts, more often than not starting with sex and moving to friendship. Robert Bremner, Bill’s model for many Drum Strips made for the American S&M magazine Drummer, and my friend, died from AIDS in 2003 (see under the Seedboxes). Being HIV+ myself, the weight of so many losses helps drive a determination that my alternative family tree should not be destroyed by vagaries of memory and prudery. I have carefully researched the particular stories and characters of his work and studio stamped them. On an artist’s death work that remains is often unsigned. In Bills case many were working drawings and in any case an illustrators work would be ‘branded’ by the layout artist so that signatures were actually discouraged.

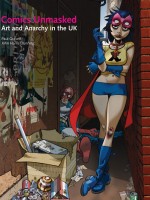

A queer kinship network saved Bills’ archive initially but, similar to the urge to reconstruct mainstream genetic family trees beyond immediate relatives, I feel a duty towards the wider alternative queer family’s legacy. I have stored and researched into Bill’s archive, nevertheless, I have found just as Brian expected, that it is extremely difficult to disseminate such material. I briefly managed to contact Bill’s great niece who helped fill in some biographical details. In 2014, as a result of noting Bill in my previous website, I was able to provide Paul Gravett and John Harris Dunning with background information in relation to ‘Comics Unmasked, Art and Anarchy in the UK’ at the British Library (May-August 2014), which featured Bill as one of two gay erotic comic illustrators (see pages 127 & 128 of the accompanying book). Mainstream archives have only recently begun to examine how they classify and value alternative cultures and to a large extent the only reason such stories are told or saved is because people like myself refute established criteria but also through loyalty to our tribe. Through intimacy with Robert I am intimately ‘related’ to Bill (Robert was a ‘bear chaser’) though I did not know him; through Bill I can touch the photographers and illustrators who helped create my own queer cultural identity.

I would be very happy for interested parties to contact me regarding the archive. I would be delighted to facilitate anything, including loans, that gets Bill better known or that helps with LGBT studies. If interested please contact: billward@guyburch.co.uk. A version of this text, but focusing on an album of Bill Ward’s physique photographs, appeared in Culture & Photography (see under Writing).