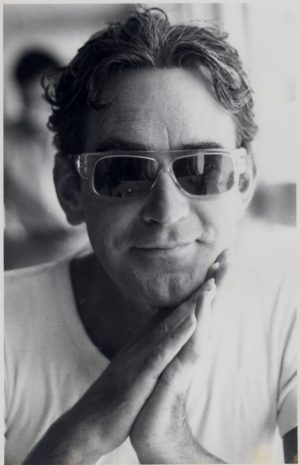

Ossie Clark 1942-96 – The Broken Butterfly

Ossie had first met Nick Balaban at the Sombrero club in Kensington where Nick was working as a barman. For most of the Eighties they lived together in a house loaned to them by Chelita Secunda, the wife of Mark Bolan’s manager Tony Secunda. Ossie had helped get her off heroine, locking her in her room at one point to do cold turkey. She had moved to the Caribbean to keep away from the drug lifestyle and Ossie filled her house with the remnants of of his past affluence, supplemented by new treasures, often s lightly dishevelled or moth eaten, from hunting expeditions on the Portobello road. Oriental carpets and Lalique glass, Hockney prints (he hid a few stained and unsigned pulls from his creditors in their frames below drawings by his children) and Vogue photographs, fought for space with piles of clothes, dress patterns and two King Charles spaniels appropriately named Oscar and Bosie. Reports of Ossie’s death made great play of the fact that he was living in a later squalid flat which was ‘artistically neglected’. Actually this was Ossie’s normal standard of house-keeping. Wonderfully gifted, but utterly impractical, for Ossie orderliness mattered little, but style mattered a lot. If it was a choice between eating or having his shirts laundered he (and Nick) went hungry. When Nick left him and when my partner Richard was in America on a six month sabbatical, we regularly met to ‘do’ the market and afterwards in return for a bit of a tidy, picking pins out of the rugs and hovering, he would cook dinner for me.

Though Ossie was certainly depressed by his divorce and bankruptcy, he and Nick lived happily together for about as long as he and Celia had done before. Money and space were in short supply but his imagination remained as fertile as ever. Commercial dress-making had lost much of its appeal but he continued to make wonderful, uniquely inventive one-off commissions for a small number of loyal friends who paid by barter: a ticket to America or his monthly bills. Not long before his death he had made an Indian wedding dress.

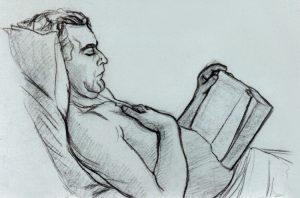

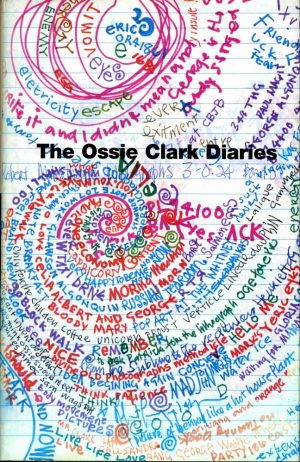

Writing became very important to him too, as he chronicled his life in extraordinary Pepysian diaries beautifully written in different colours and often decorated with delicate drawings. The people captured in them were sometimes asked to add comments of their own: Mark Bolan had added a poem about death not long before his own.

In the last few years Ossie had talked about publishing these diaries. But partly because he was a perfectionist and partly because he loathed ‘kiss-and-tell’ celebrities, he never got round to it. He had often been asked to tell the intimate sex-and-drugs secrets of those many friends who remained famous long after Ossie’s renown started to fade, but he always steadfastly refused. He remained loyal even to those who, it seemed to me, showed him little generosity once he could no longer shower them with dresses or champagne. The glitter that Chelita put on Bolan’s eyes and launched Glam Rock, and the whole 1970’s glam in general, disguised a very tough commercial world not at all given to generosity or artistic support. I saw very little help come his way from others; some who had been artistic heroes of mine seemed almost callously unmoved. Many of the women he introduced me from that time were tough and rhino skinned having survived being thrown aside or commercial falls themselves on many occasions. I liked a lot of them for it: I’ve always rather despised women who are cutesy or doting on men, preferring the Barbara Hepworth’s to Marilyn Monroe’s).

Women like Pauline Fordham who had been addicted to heroin for a decade and would keep disappearing to chase the dragon in toilets (not injecting was the secret she reckoned to surviving). It was the other fallen figures who helped him rather than those who achieve huge success (with the exception of Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour). During the whole period I knew him, he struggled to get old associates to give him, say, even a few hundred pounds to repair one of his two professional sewing machines without which he could not work. The price of a pair of shoes, the proceeds of minor drawing, or a flash dinner, they thought was wasted on him, but without his machine he could not work. Under the sixties veneer of loveliness was a very hard and cynical commercialism that hated above all the failure. Some of the distain for Ossie and his crowd came ironically from those cashing in on Punk. Vivian Westwood and Malcoln Maclaren produced a t shirt in blue and red headed ‘You’re Gonna Wake up One Morning and Know What Side of the Bed You’ve Been Lying On’. Produced in 1974 it features text devised by Maclaren with ‘Hates’ listed on one side and ‘Loves’ on the other. It had ‘scum’ scrawled over a list of hates that included David Hockney (for “Victorianism”) and Ossie along with many others of their milieu including Chelita Secunda and Andy Warhol. Pauline is listed as “Pauline Fordham halitosis”. Both these two, were it not for a dislike of the whole tasteless idea, would be on my list of hates.

But it was actually his break up with Nick Balaban which really depressed Ossie in his latter years, not some maudlin pining for the Sixties or his past life. Nick had been young when they met: as he grew older he developed as an artist and even started his own fashion business selling his marvellous graphic t shirt designs to Reiss, Top Man, BHS and boutiques). He needed the space and calm away from the turbulent wake Ossie tended to leave, to find his own voice.

Ossie was devastated and his world fell apart again. For two years he stagnated in a state of total depression always hoping Nick would return. For a time he lived with me in an Islington council flat Nick and I had (Nick moved in with a new partner). They remained in contact and gradually Ossie was reconciled to this second ‘divorce’. In 1991 Nick was diagnosed with AIDS and depression descended again. Nick had also become disenchanted with fashion selling his share of the business (Balaban and Nota Bene) he had started and returned to painting. Ossie encouraged him all he could but the effects of the virus were becoming more and more debilitating. Finally Nick was diagnosed with CMV and blindness slowly descended. It is difficult to imagine if you have not experienced it the sense of helplessness this engenders. Nothing could change the diagnosis at the time and efforts to support him were thwarted by new infections and indignities. The experimental drugs were horrible to administer and caused as many problems as they aimed at solving. At the end love was what Nick needed and Ossie gave it to him.

With Nick’s death in 1994 Ossie slowly let go of the past. Now in a tiny housing association flat, it began to be filled with new drawings and designs. Re-appraising his old work he was searching for a new silhouette for clothes. Working for Bella Freud and Ghost his genius for bias cut and difficult material were gaining him recognition again. With new boyfriend Diego, and the promise of financial backing from David Gilmore of Pink Floyd, it looked as if his star was rising again.

Unfortunately the mundane world came crashing into the enchanted one he was busily spinning around himself. After too much champagne at a fitting session he impatiently nudged the car in front of his at a petrol station which unfortunately contained an off duty police officer. A van load of reinforcements arrived and both Ossie and Diego were arrested in a messy scene reminiscent of Absolutely Fabulous. Ossie was very like Edina Monsoon and Patsy Stone all rolled into one (the series is really a disguised portrait of his circle even down to the celebrity Buddhism that actually enormously helped Ossie find his feet). Probation for Ossie and community service for Diego followed. Stress of the court case and living together in Ossie’s tiny flat together with money worries took their toll. The relationship, disapproved of and unsupported by many of his straight friends and family, began to unravel. Ossie had used up his nine lives and disaster followed when Diego, high on drugs and ‘hearing voices’ from the Devil, smashed in Ossie’s skull with a flower pot.

The ‘turbulent and ultimately tragic life’ of a ‘flamboyant homosexual and drug user’ as the Daily Mail’s Edward Verity put it, is not what I will remember of Ossie. I will remember a man who transformed the mundane world into an enchantment, who could make something from nothing, turning Sobranie cigarette packets into a intricate, mystically inspired mosaic inlay for his Buddhist shrine (“Look darling isn’t it fabulous”). It will be sad indeed if this wonderful, chaotic sometimes impossible man who was talent and fun incarnate, who could cut a dress for Liz Taylor freehand whilst pissed at 2am, were remembered only as a broken butterfly of the sixties.

I’ll remember him draped in a cashmere throw smoking a joint on the walk of the council flat in Islington and charming the neighbouring drug dealers. I’ll remember arriving from college with Nick at Chelita’s house to find Ossie in the kitchen. On asking what he’d been doing he said “oh Pattie’s here – we’ve been doing a fitting”. The next moment Pattie Boyd, wife of George Harrison and Eric Clapton (she is his ‘Layla’), burst through the door wearing the only the intricate armoured canvas corseted structure that held his strapless dresses in place. Her very ample breasts, like two large milk jellies and wobbling worryingly (you can tell I’m gay can’t you) in the structures Ossie had made for them, were thrust into my 19 year old face for assessment. I’ll remember a Christmas eve in which Francesca (Chessie) Thyssen-Bornemisza was thrown on the messy floor of yet another loaned flat in Fulham and strewn with tulips for a polaroid image that later featured in the posthumous V&A exhibition. Afterwards Ossie, who was hoping to gate crash a David Sylvan party with her, tried to follow her fast car in his loaned and unlicensed bubble car with me as a passenger. Pathetically slow, he was forced to jump a red light and turned almost hitting a police car. Parking as they turned to pursue he said “just walk away darling, pretend nothing happened”. It didn’t work and after waiting for several hours for an (of course) over the limit ‘Raymond’ Clark I was forced, having missed the last trains, call my father to collect me and Oscar. Ossie arrived two days later and charmed the pants off my parents.

Like many extremely talented people he could also be hideously difficult, shouting at a waiter who vulgarly tried to shoo out party guests, referring to black me with the (very 1960s) ‘spade’ or his anti-Semitic comments on ‘jew boys’. This last stemmed from what he regarded as deviousness of a Jewish business partner. Nick told me that in his usual scatty way he had been asked to sign a document as he hurried for a plane and this turned out to make him personally liable for his companies debts, placing his house and all his possessions in the hands of the tax man and creditors. He had also become violent as his marriage ended. The famous Hockney painting of Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy’ is a portrait of a three way affair and Ossie does not look comfortable in it. Like the business deal he allowed himself to sign up to what everyone thought was a good idea on paper. Everyone knew he was gay but a marriage of friends was encouraged by all. When I first met him I asked him about his sexuality and he said “Oh darling I’m just highly sexed”. Separated from Celia and living an entirely gay life I thought it telling when he reported telling a doctor “I’m gay”: several of the sixties people I knew, whilst apparently swinging, were actually still highly affected but the morality of their parents and the possible repercussions of being out in ‘society’ made them conservative in acknowledging their sexuality publically.

I’ll remember seeing the fashion show for Radley Gowns in the mid-eighties where dresses with sleeves like sea shells just stunned me. Gasping a one particularly Baroque example he said “Oh you like that one – I cut it out at 2am this morning, isn’t it devooo darling.” Or the sex party at Cynthia Paynes house – exactly like the film version in ‘Personal Services’. I’ll remember also Nick saying “do you want to see the Hockney painting?” and being taken upstairs to a cupboard in the attic. Scrunched up and very battered inside was the upstretched canvas ‘Life Painting for a Diploma’. Hockney had pulled it off the canvas after using it to fulfil the Royal College requirement, kept the drawing of a skeleton attached to it, and thrown the painting away. Ossie, thinking he might use the canvas in a dress reclaimed it. Some years after seeing this sad remnant, a man approached Ossie at a party to say he had the skeleton drawing and wondered if they might come together. The process of reuniting the two, restoring it (miraculously) and bargaining with Hockney to recognise it, Ossie told me resulted in no benefit to him at all. It eventually went to the Tate Another of his cunning plans that resulted in nothing to lift his status.

When his friend Lady Henrietta Rous, one who always tried to help him, edited The Ossie Clark Diaries (1998) I was horrified at the selection from his later years picturing all the gloom but not the fun. Even more upsetting was that Nick was not pictured at all: expunged in favour of the ‘real’ family and celebrities it felt cruel. The same followed in various articles and books that resolutely focus on the ‘heterosexual’ man (I could at least alter his Wikipedia page to balance things). I have very mixed feelings now when I see his vintage outfits sell at hundreds of pounds knowing he struggled to find buyers for a made to measure little black dress at £200 when he couldn’t pay his rent. For some of us he continued to inspire as he fluttered his bruised wings. In a world full of caterpillars it takes balls to be a butterfly.

An edited version of this text was previously published in Gay Times shortly after Ossie’s death.